"Same reason Mallory climbed Everest," Sanjay says. "Because I can."

"What are we going to tell our backers?" she tells Sanjay later in the story. "They're paying us for science, not for stunts."

Sanjay makes the trip personal. "Humans see different things than drones do," he says.

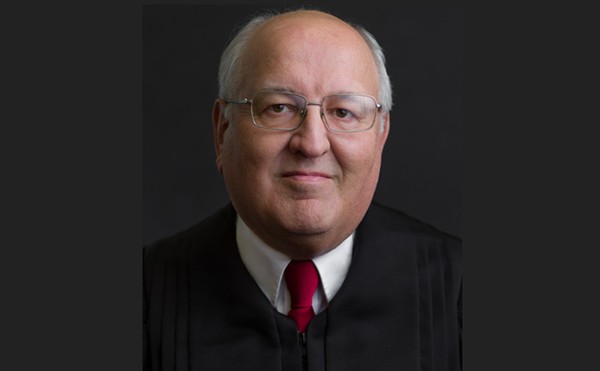

The vision and risk in Landis's science fiction, like in that 2022 short story, are barely contained to the realm of make believe. Landis, besides being an award-winning novelist and fiction writer, is an aerospace engineer at NASA Glenn, which has gifted the now 69-year-old a reciprocal gift in by-day and by-night lives: interplanetary research that feeds into his writing; writing that foreshadows his research.

Research that has led Landis, since the late '80s, into aiding some big projects. Into building sensors on the iconic Mars Perseverance rover. Into investigating dust-gathering instruments for NASA's Pathfinder probe. And now, after decades juggling the real and the speculative, Landis and a team of engineers are working to figure out if, you could say, the idea behind "Cloudskimmer" is possible.

That is to say: Can we land on the surface of Venus, and take some surface home with us?

And billions of years of a mega greenhouse effect has made flying anything below orbiting level a chore. Only the Pioneer Venus 1, in May of 1978, was able to fly into the planet's atmosphere, and record useable data to bring home. Namely, a map of Venus' surface scientists still use today.

"That's why Venus is sort of the ignored planet," Landis said, sitting in a chair in NASA Glenn's engineering room where designs for space missions dot the walls. With his scraggly white-and-orange beard and clear specs, Landis gives off vibes of grizzled academic and earthy scientist. "Well, mostly because it's really hard. I mean, we think Mars is hard. But, you know, getting down to Venus' surface is really hard."

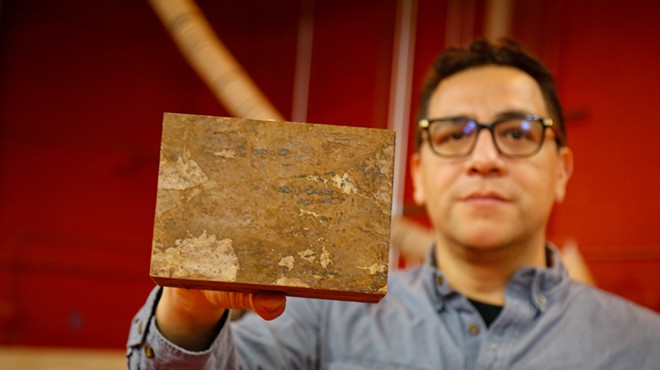

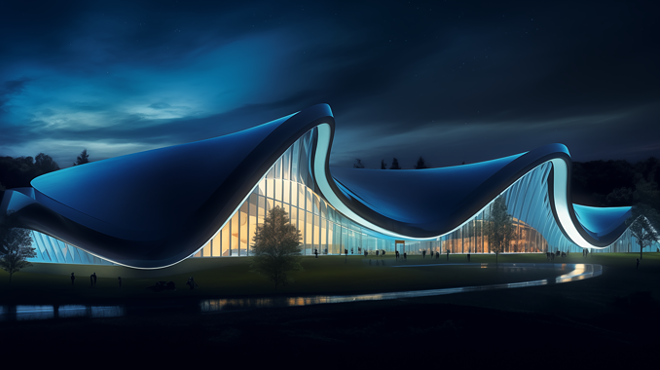

Landis and his team of 14 are proposing a workaround based in 21st century technology: use a solar-powered aircraft built with electronics that can withstand high temps—with tough motors, cameras, microcontrollers—that will glide to Venus's surface and pick up rock samples to study. Then, mixing helium and carbon, be balloon-lifted up to a rocket, which will itself use carbon dioxide to rocket the Venus soil back home to earth.

But why? With NASA's Artemis Mission, and its projected price tag of $93 billion, the U.S. space industry, both public and private, is nearing an era of trials that will determine the ifs and hows of hosting human beings longterm on other planets. And also, as has been the case for centuries, delve more into the actual origin of our solar system.

“Our knowledge of the geology and mineralogy of surface of Venus is mostly hypotheses, with little 'ground truth' supporting the hypotheses," Landis, and his colleagues Steve Oleson and Anthony Colozza, write in their white paper to be presented at the end of July. Despite the intrigue, finding truths via Venus's rock samples remains "a tremendously difficult problem."

Which is why, a pessimist or a negative engineering study may say, Landis' dream of landing on Venus may stay in the realm of science fiction.

Or at least it'll keep Landis at the writing desk. That same intrigue that led Landis to score both the Hugo and Nebula awards for a debut science fiction novel for his 1992 pre-Matt Damon expedition of the red planet in Mars Landing. Or to speculation of floating cities in the Venus sky, as in the story "Sultan of the Clouds" that landed him on the cover of Asimov's Science Fiction magazine.

While some may read an H.G. Wells or a Philip K. Dick story as pure entertainment, Landis doesn't seem to separate the useful from the lofty. In a way, the act of writing a space drama set on Mars is a thought exercise that, there at Building 77 at NASA Glenn's campus, pushes Landis to find the right physics principles to build the drama, per se, for real.

He thinks of comparable examples, influences of the budding writer in grad school, Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Heinlein. How Heinlein practically invented waterbeds. How Clarke invented the geostationary satellite.

"Science fiction is the inspiration. Science fiction looks at both. What's possible that would be cool. And what do we want?" Landis said. "And also looks at what's possible that we really don't want—a dystopia that we want to avoid."

Subscribe to Cleveland Scene newsletters.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter